Think of your business as a car.

To start and run efficiently, it needs two things: energy and upkeep.

According to WalletHub’s 2019 survey, small business owners’ “biggest frustrations” are (1) acquiring customers and (2) accounting basics like cash flow, expenses, and taxes. New and existing alike, customers fuel your business.

But more gas doesn’t make the car last longer. It’s the knuckle-scraping ongoing maintenance that keeps the car running for years beyond it’s expected life.

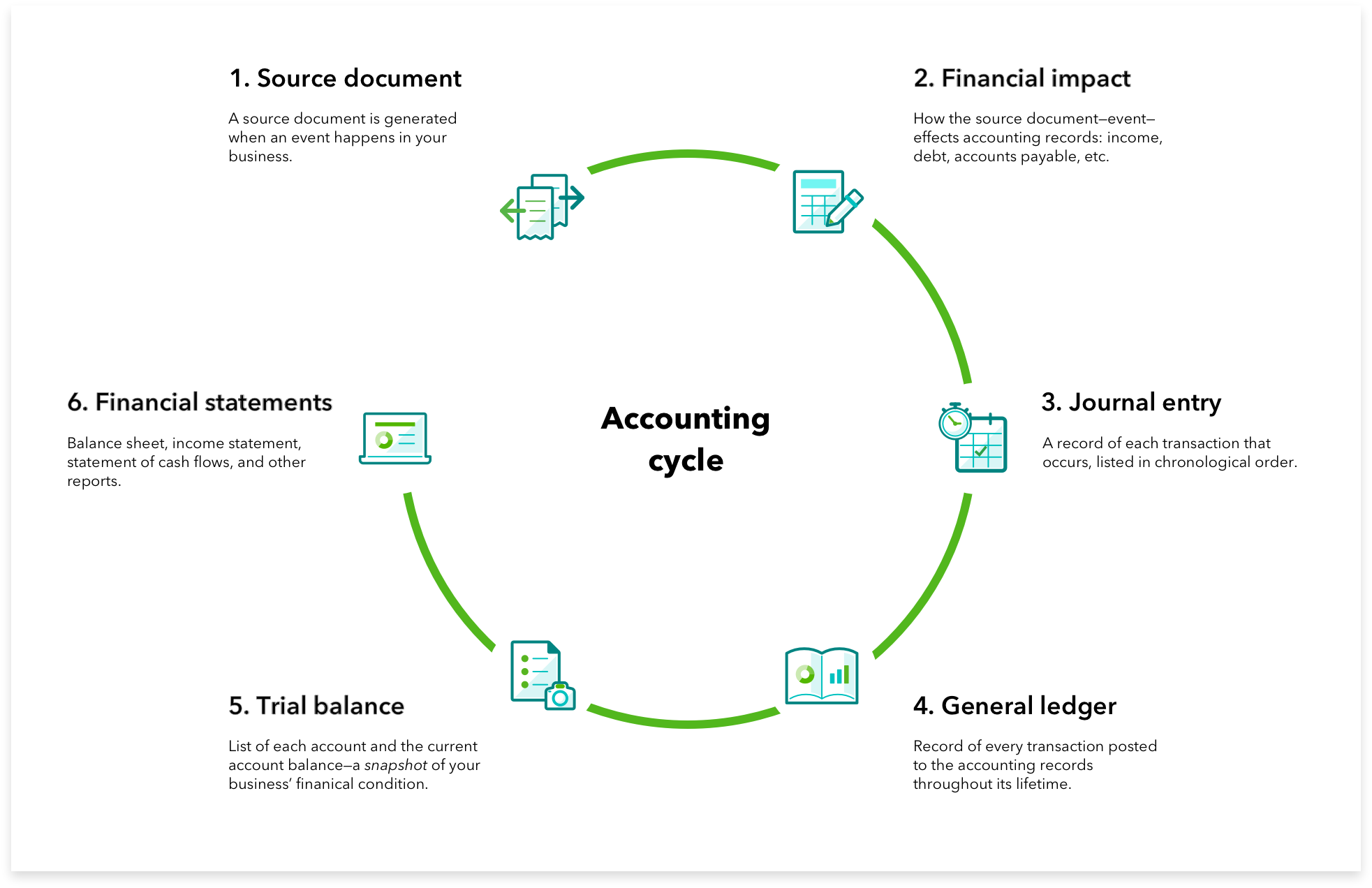

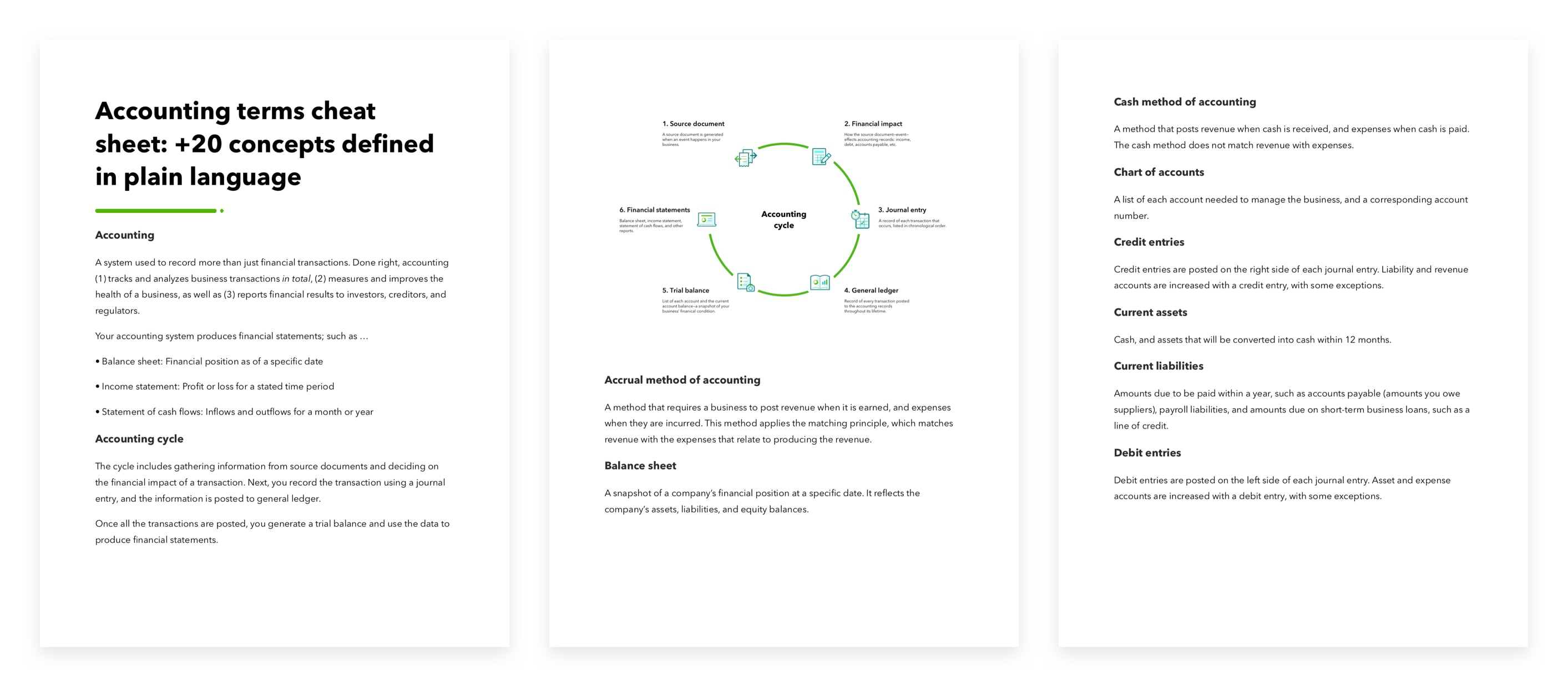

In a similar way, a well-managed accounting system keeps your business running each day. It’s a process that gathers information, puts it in the right place, and reports useful information to you.

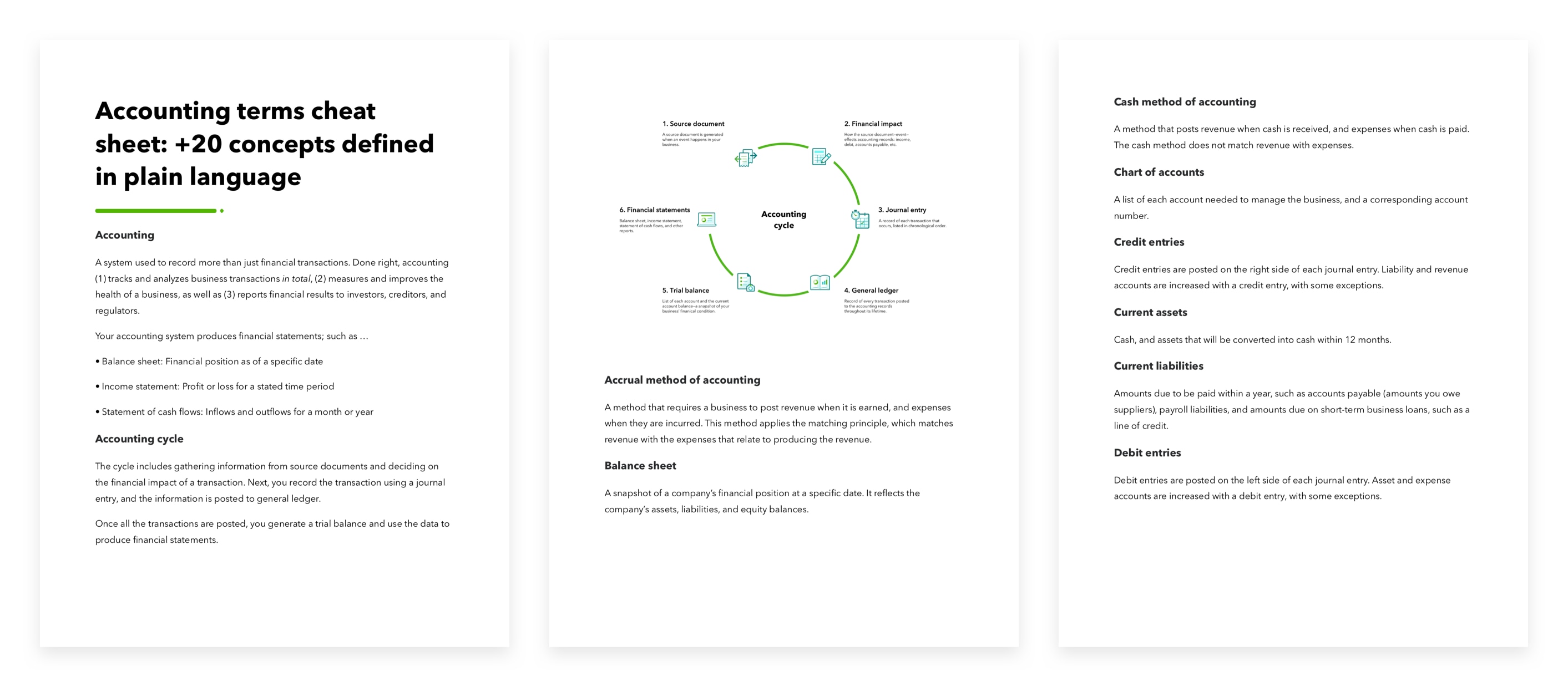

(You’ll see a more detailed definition of accounting below.)

To keep your car on the road, scheduled maintenance is a must. The same is true of your accounting system.