You made the made the sale! Put it in the books, deal closed, right?

Well, maybe.

The deal might have closed, but that doesn’t mean you’ve actually made any money. Once you deliver your product or perform your service, and deliver the invoice, now you have to collect on that invoice.

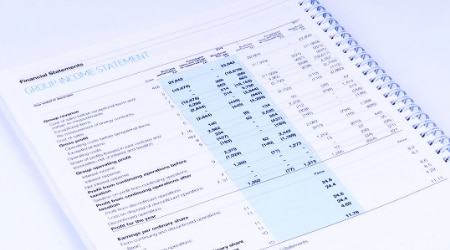

On paper, collecting on an invoice seems simple. You delivered the product or service to the customer along with an invoice which states the work performed, the associated costs and the due date for the payment. Now it’s your customer’s turn.

While simple on paper, this basic and fundamental business process known as accounts receivable can help boost a business’ ability to transact more business, but it can quickly become a pain point if it’s not managed effectively.

Money owed to a company for work performed is known as accounts receivable, often called “AR” for short. On a balance sheet, accounts receivable are categorized as an asset since they (in theory) will become cash in the future.

As the definition indicates, accounts receivable arise when a business sells its good or service to a customer on a credit basis—i.e. the customer is not required to pay at the time the good is delivered or the service is rendered. Transacting business on credit can make it easier to secure new work. Customers get the benefit of obtaining the good or service now, but not having to pay for the good or service until later. While this may help close more sales, offering credit to customers does create some risk for the business.

The most obvious risks to maintaining accounts receivable is the risk that you might get paid slowly or—worse—not paid at all. While you can book a sale on your income statement , you must also increase the amount due from customers. While accounts receivable is reported as an asset, if the accounts receivable is not paid, it becomes a “bad debt expense.” The bad debt expense is recorded as a bad debt/credit loss on the income statement and a simultaneous reduction of the accounts receivable asset.